A 9/11 reflection from Franklin to New York City

Published 10:11 am Saturday, September 11, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Twenty years have passed since a 31-year-old Don Wilson went from hearing, in Franklin, about the Sept. 11 terror attacks to assisting with the recovery operations in New York City shortly thereafter.

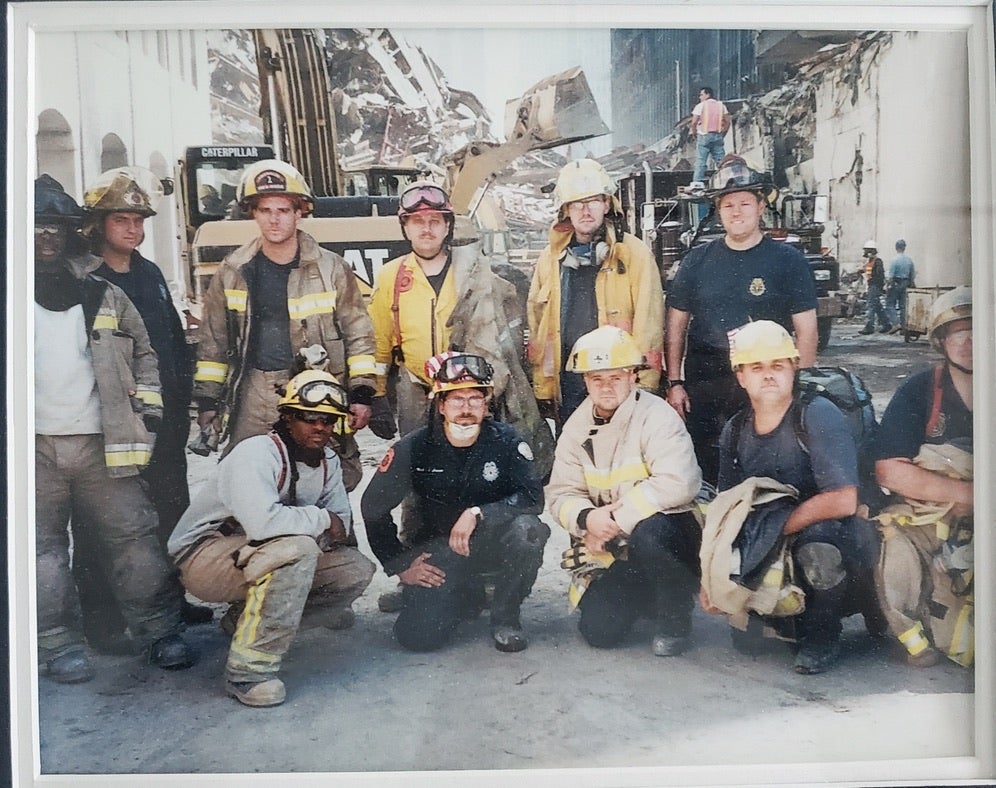

Wilson, now a captain in the Navy who lives in Ivor, is one of 12 area firefighters for whom the sights, sounds and smells of ground zero are still fresh in his mind.

He highlighted the importance of reflecting on 9/11 since a younger generation of Americans now exists that had not been born when almost 3,000 people were killed after 19 militants associated with the Islamic extremist group al Qaeda hijacked four airplanes and carried out suicide attacks against targets within the U.S.

“I’m originally from Jersey City, New Jersey, right across from New York City,” Wilson said.

He noted that he grew up watching construction of the World Trade Center and seeing the World Trade Center basically every day of his life when he was a young child and a teenager. He could see it from his room, from his high school, Saint Peter’s Prep, and from where he practiced football at Liberty State Park.

“And when I left Jersey City in 1987 to join the Navy, I traveled all around the world,” he said. “The Navy brought me to Franklin in August of 1996. I lived on Norfleet Street.”

It was 1996 that he also became a volunteer member of the Franklin Fire & Rescue Department.

Later, the Navy took him abroad.

“For almost two years, I had been in the western Pacific, and my last tour at that time was in Japan, and I had transferred back to the United States,” he said. “I was moving back into my house in Franklin, and this is right at the end of August of 2001.”

He had 30 days leave, and the weekend of Sept. 7-9, he visited New Jersey and New York City with his two oldest sons, and they all even went to the base of the World Trade Center.

“That’s just something I always think about is that, timing-wise, if it would have been a couple days later, I might have been up there if school wasn’t in session, because at the time I had family up there,” Wilson said.

However, his kids were back in school come Tuesday, Sept. 11, and with nothing to do in the daytime while on leave, he opted to serve a volunteer shift for Franklin Fire & Rescue.

He remembered washing Engine 5 that morning, a fire truck that he said is still in service with the city.

“I’m washing that truck, and at the time, the shift captain, Ronny Griffin, comes outside and says, ‘Hey, Don, you grew up right across from New York City, right?’” Wilson recalled. “I said, ‘Yeah, I did.’ He goes, ‘You should come in here. A plane hit the World Trade Center.’

“And I’m like, ‘Yeah, let me finish this, and I’ll be in.’ And in my mind, I’m thinking it was like a small aircraft or like a helicopter, right? Just not thinking it’s that big of a deal, maybe it’s foggy up there, whatever.”

He ended up finishing his task outside.

“And then I walk into the day room, and that’s a big screen in there, and I was in shock at what I saw on the screen,” Wilson said. “Here’s a building, and there’s a big hole in it, and there’s fire and smoke. I’m like, ‘Holy cow,’ right? And as I’m trying to process all these things in my mind, the second jet hit. And I mean, just completely shell shocked, all of us.

He said he and his fellow Franklin firefighters were glued to the TV.

“Over a period of time, more people start coming in that are members of the fire department,” he said. “And we’re watching this, and at the same time, we’re getting the reports of what’s going on in Washington, D.C., we’re getting the reports of possibly additional hijackings, things like that.”

He said everyone at the fire station could not move.

“We can’t really say much except we’re full of questions that have no answers,” he said.

The first World Trade Center tower fell and then the second.

“None of us had ever seen anything like that live before, you know what I’m saying?” he said. “How do you process something like that?”

He said that if he remembers correctly, “I don’t think there was a call at all that day for us. I don’t remember ever leaving the station and going on an EMS call or on a fire rescue call.”

An ensign in the Navy at the time, Wilson said, “I’m calling back to the people who move us around going, ‘Do you need me someplace?’ And they’re like, ‘Stay put. Just stay on leave.’”

He said he tried to call family and friends up in New York.

“This is well before social media,” he said. “We had email, but we didn’t have Facebook. So I’m trying to call people to find out, because I knew people that worked in lower Manhattan, that worked in the trade center, guys I went to high school with. And again, nobody’s got any information.”

He explained that Franklin Fire & Rescue had already had an exchange program with the New York City Fire Department, and Franklin’s fire chief at the time, Dan Eggleston, had ties to the New York City Fire Department.

“That evening, Dan Eggleston had called us all together and said, ‘Hey, I want to send a team up north, and I want to send about 12 people up north, various firefighters with rescue experience from Franklin and from the surrounding county fire stations,’” Wilson recalled. “And he looked at me, and he said, ‘Don,’ he said, ‘Can you get us in there?’ Because I’m from there, so I know all the roads, I know all the ways in, because lower Manhattan’s completely shut down, the Holland Tunnel is shut down. So he goes, ‘Can you drive one of the vehicles, and can you get us in there?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah.’

“I was kind of in shock that he asked me, because like I said, I had just come back from being gone for almost two years, and I felt that there were other deserving firefighters that probably should have went ahead of me, but call it resident knowledge, whatever.”

On Sept. 12, the group of area firefighters outfitted two vehicles — a Suburban and a van — with gear and started the drive up in the late afternoon. Wilson drove the lead vehicle on the trip.

“We had a police escort for a good portion of it,” he said. “People were getting out of our way, and then there were other emergency vehicles headed north too.

“So we get up there, and I get us over into Manhattan, and there’s a blockade for the West Side (Highway) going down into lower Manhattan,” he continued. “We have emergency vehicles, we’ve got lights, sirens, they let us through, just go, go, go, everybody’s pushing us through.

He said the further they got south into Manhattan, there was no power in the area because all of it had been shut off.

“So it’s very dark,” he said. “The other thing we noticed is it looked like it was snowing. So windows are still up, we’ve got the AC on.”

He said there were vehicles all over the place.

“You’ve got to remember, they evacuated lower Manhattan, so in the middle of the street, there’s still cars that have been abandoned, trucks, things like that, buses,” he said.

He noted they parked probably five or six blocks away from the World Trade Center on a side street where a pizza place was located.

“Then when we got out of the vehicle, there was the ash coming down,” he said. “There was this eerie silence, and there was this scent or this smell in the air that I cannot describe to you. I can remember the smell, but I can’t describe it to you. It was like a nuclear winter. It was something out of the apocalypse, out of a movie, it was unbelievable.”

The Franklin-area firefighters put on their backpacks, grabbed their gear and started walking.

“As we get closer, you can see the glare of the lights, because down at ground zero, there’s floodlights all over the place,” Wilson said. “World Trade Center Building No. 7 was still on fire. There were other fires that were still going on.”

He said they finally came around a block to where the familiar sight of the World Trade Center towers had greeted him for so many trips into the city throughout his childhood and teenage years.

“There’s nothing there,” he said, recalling the scene in the early morning hours of Sept. 13, 2001. “It’s just smoke, it’s still ‘snowing,’ it’s just sounds of equipment and alarms going off. It was crazy.”

And operations at ground zero were completely disorganized as well, he recalled.

“We didn’t know where to go,” he said. “Remember, we didn’t do a formal request that said, ‘Hey, we’re coming’ or anything like that. We just showed up.

“And then it starts raining,” he continued. “And then something else happened where this big alarm went off, and they ordered everyone to stop on the pile and just break away. I don’t remember if it was they were afraid it was going to collapse or if it was a gas leak or what.”

On a street corner, the Franklin-area firefighters ran into colleagues from, of all places, a Chesapeake fire department that had also sent a team.

By this time, it was probably 1 or 2 a.m., Wilson said, so the area firefighters took a catnap right there on the sidewalk underneath a covering.

Early that morning, Wilson and a few others walked around the perimeter of ground zero.

“There were food trucks set up that were providing hot meals for all the rescue workers and stuff like that,” he said. “We go grab something to eat, and we continue walking around the perimeter and (see) just the total devastation. Everybody is just looking like they’re in shock. Everybody has just got these wide eyes (that say,) ‘What is going on?’

“You could see some New York City firefighters, and you could just tell the pain that they had, and you know, you didn’t say anything to them. Everything was just, ‘Hey, brother,’ ‘Hey, brother,’ that kind of stuff, but you could just see the devastation in their faces, the loss on their faces.”

Wilson also recalled a key feature from his many visits to the World Trade Center.

“There was a courtyard between the two towers where there was a cafe, and there was this big, bronze, globe-looking thing,” he said, noting it historically had music that was playing over loudspeakers there, kind of like elevator music. “Really strange, but that music was still playing. … How it was still playing I don’t know because there wasn’t any power. I just remember there wasn’t any power except for the generators.”

Wilson said that after returning to the street corner where he had slept, Chief Eggleston had found out where the New York City command post was.

“We reported in, we told them who we were, and the first thing they assigned us to do was to help set up a supply depot,” Wilson said, which included things like gloves, helmets, masks for ventilation, shovels, picks and bottled water.

After completing that task, the local firefighters received an assignment to go over to West Street near where there was a telecommunications building.

“I think it was the AT&T building, and we were asked to start clearing out the debris from that area and the surrounding area there — because portions of this building had collapsed there — and to help get down to where the fiber-optic cables were,” Wilson said. “One of the priorities they wanted to do was get the financial district back online.

“So we started digging, we started removing stuff, and we had to do this by hand and with rope and pulleys that we had, because there was no heavy equipment there.”

They were right next to where part of one of the towers had come down.

“There was a crew from the New York City Fire Department working nearby,” Wilson said. “They were in that rubble, and I remember that every time around us that they had pulled out a fire truck or they had found remains, especially remains of a first responder, we had all stopped.

“And the New York City Fire Department pulled out their own, and we formed an attention line with a salute as they went by, as they recovered the remains. And then we kept going.”

Wilson said the Franklin-area team never did find any remains, though after finding a woman’s shoe while digging, they were afraid they might.

Other hazards made their task difficult, including broken water lines and suspected broken gas lines.

“We had been working for almost two days, and it was time to get some sleep, and I remember they directed us over to the Embassy Suites,” Wilson said. “Somebody just told us to go find a bed. There’s no power in this building. There’s no power, there’s no running water, and the majority of the doors were open and spray painted because somebody, probably New York City Fire Department or somebody else, had gone through to make sure everybody had gotten out.

“I just remember going in this room that somebody had occupied and just crashing on a bed.”

He said he got up in the morning and went back out into the pile, and eventually everybody was ordered to stop what they were doing. They were wondering what was going on.

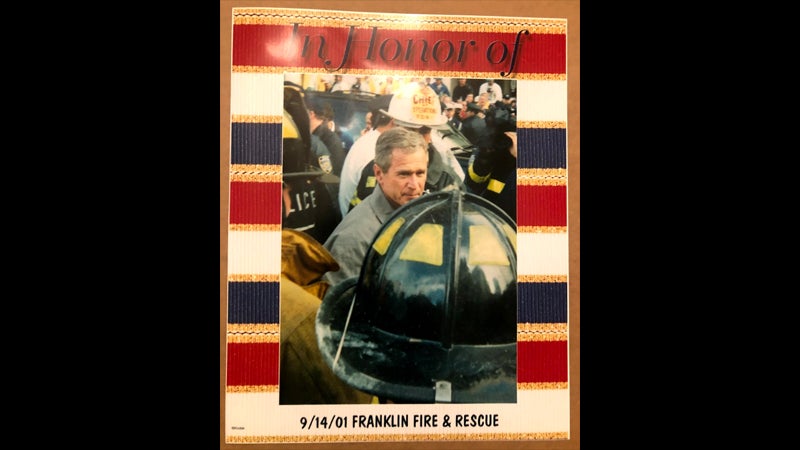

“Well, that’s because President (George W.) Bush showed up,” he said.

Wilson noted Bush was coming to ground zero with Gov. George Pataki, Mayor Rudy Giuliani and U.S. Sen. Hillary Clinton.

Completely exhausted, Wilson was sitting on a yellow crane.

“I remember fighter jets flying over New York City, and I’m just sitting there, and I see this guy, he’s next to me, and he’s wearing a Bayonne, New Jersey, firefighting jacket, and that’s the city right next to Jersey City I grew up in,” Wilson said.

He struck up a conversation with the man and found out they both went to Saint Peter’s Prep.

“And then come to find out, this is a guy I played football with in high school,” Wilson said. “Yeah, Kevin Fitzhenry, played football with him in high school. He’s a year older than me.”

That was not the last “small world” element to Wilson’s time in New York City over those days following 9/11.

“My best friend that I grew up with was operating a block away,” Wilson said, referring to Joel Skursky. “He was a firefighter in Pennsylvania.”

From the crane, Wilson ended up having a great view of Bush’s famous bullhorn speech.

When someone said they could not hear Bush, the president replied, “I can hear you! I can hear you, the rest of the world hears you, and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”

Wilson said the crowd roared so loudly at that line that it reminded him of being at a raucous pro wrestling event.

“It just lifted everybody’s spirits up,” he said. “I was too tired to try to walk down and shake his hand or shake any of their hands.”

After Bush and the elected officials left, digging and debris removal operations resumed.

“Then I want to say it was another day, and then all of a sudden, we were told to leave,” Wilson said. “All the fire departments that were not from that area, a New York City Fire Department representative had gone around and just about basically ordered us all to leave. Something about it being a crime scene. They wanted construction guys to come in.

“I kind of think it was the union taking over. I think at that point, they had probably figured out, ‘Hey, we’re not going to find anybody else at this point. It was just recovery.’ And they wanted some kind of control over the area.”

The Franklin-area firefighters packed up their gear after about 96 hours of operations and drove back toward home.

“We were filthy, we were absolutely filthy, and I know we all stunk,” Wilson said. “We stopped at a rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike, and we walked in to just use the bathroom and to get food to eat. We walked in and all these people stood up and just started clapping for us.

“And that was really hard for me and for the others,” Wilson continued. “It was kind of like, we’re nobody, we tried to do something, and we didn’t rescue anybody, you know what I’m saying? The manager paid for all of our food, just gave us food, we couldn’t pay for anything. People were giving us money for the fire department. It was really weird. I told Chief, ‘I’m not taking anybody’s stuff. Here.’”

When Wilson got back home Sept. 17, he said he finally showered, probably staying in the bath for a long time, with big questions running through his head.

“What did we just witness?” he said. “What were we just a part of?”

“Just the sights of the destruction, the smell, the eeriness, the sounds, man, that’s stuff I’ll take to my grave,” he said. “For me personally, to just be a part of that because of where I grew up and what I saw, it was kind of surreal.”

In 2007 with the Navy, he had his first combat deployment to Afghanistan, and then he went back in 2010, helping to take the fight to the soil of those who engineered the 9/11 attack.

He noted that in 2009, he was fortunate enough to be assigned to the U.S.S. New York, a Navy warship built with World Trade Center steel.

He went to New York City for the commissioning ceremony in November 2009.

“That was just very powerful, that, ‘Hey, OK, you took something from us, and guess what? We rebuilt. We’re rebuilding this big, giant tower and this complex there, and we’ve built this warship that’s got seven-and-a-half tons of World Trade Center steel on it,’” Wilson said. “So that was pretty intense and pretty special.”