Franklin scores poorly in university health study

Published 1:38 pm Saturday, March 24, 2018

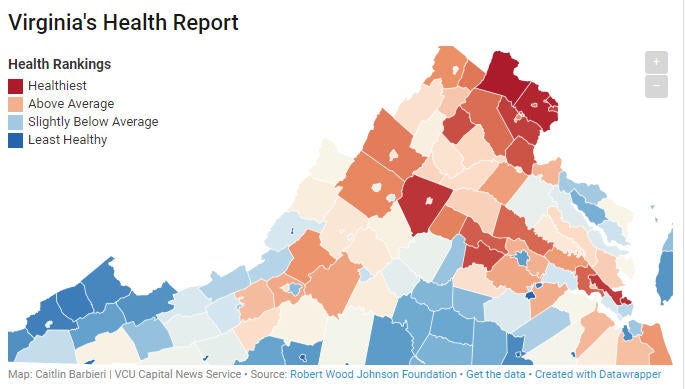

- Virginia's health report

FRANKLIN

The City of Franklin has once again fared poorly in the University of Wisconsin’s annual study comparing the health of cities and counties in each state.

The university’s Population Health Institute released its 2018 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps report in March, which examined the average health outcomes for each municipality based on residents’ life expectancy, overall quality of life, health-affecting behaviors such as smoking and physical inactivity, access to clinical care, socioeconomic factors and environmental considerations.

Each municipality was then ranked on a scale of one to 133, this being the total number of counties and independent cities in Virginia in 2018, with one being best and 133 being worst. Franklin scored 127.

The most notable disparities reported between health outcomes in Franklin versus other cities and counties in the Commonwealth were the city’s rate of premature death, the number of new sexually transmitted infections diagnosed and the number of teen births.

Premature death, defined as the number of years of potential life lost before age 75 per 100,000 people was reported to be approximately 11,800 in Franklin, compared to 6,100 statewide. Ali Havrilla, a community coach with the university’s County Health Rankings and Roadmaps office, explained that these figures had not been adjusted to take into account the fact that Franklin only had a total population of around 8,500, and so no conclusions could be drawn for exactly what percentage of the city’s population was dying before age 75.

“We have been producing the rankings for almost a decade now,” she said. “What they illustrate is where we live makes a difference on how long and how well we live.”

She added that this year’s report had for the first time broken down several metrics by race. The racial breakdown for Franklin’s premature death metric indicates that while the number of years lost before age 75 for white residents was only slightly higher than the state average, coming in at 6,500, the average for black residents was significantly higher, coming in at 14,700.

“Segregated communities of color are more likely to be cut off from opportunities for health so it’s really starting that conversation and identifying what are the opportunities for action,” Havrilla said.

The study’s analysis of new sexually transmitted infections diagnosed annually focused on chlamydia cases per 100,000 people, reporting this figure to be 1,067.3 compared to a statewide average of 424.5. A graph displaying the city’s year-to-year trend for new infections, however, showed that the figure reported for 2018 was significantly lower than the 1,397 infections per 100,000 reported for Franklin in 2008. No racial breakdown of this particular metric was included.

“That’s a way the rankings can be used, to help measure progress,” Havrilla said.

Teen births in Franklin, defined as the number of births per 1,000 females age 15-19, was reported to be around 50 — more than double the statewide average of 21. Like premature death, this particular metric included a racial breakdown, with an average of 34 reported for white residents and an average of 59 reported for black residents.

In terms of access to clinical care, the only significant disparity between the city of Franklin and the rest of Virginia was in the number of mental health providers. In Franklin, it was reported that there is currently one mental health provider for every 1,190 residents, while statewide, the ratio is 680:1. The report indicated there is an above-average ratio of primary care physicians to residents in Franklin, 850:1compared to 1,320:1 statewide. The ratio of dentists to people in Franklin was reported to be 1,660:1 compared to 1,490:1 statewide.

Preventable hospital stays in Franklin were also somewhat higher than the statewide average, coming in at 68 compared to 43. However, on average this metric has been trending downward since 2008 when a total of 185 preventable hospital stays were reported. Franklin’s rate of uninsured adults, while slightly higher than the state average, has also been trending downward since 2009.

In terms of socioeconomic factors, the study reported that the number of Franklin children living in poverty was significantly higher than the state average, 34 percent compared to 14 percent, and that the percentage of children in poverty had been rising since 2002. It has dropped slightly in recent years, however, from its peak of 37 percent in 2013.

“Social and economic factors are actually 40 percent of what contributes to overall health outcomes so they’re really important,” Havrilla said.

By comparison, most health outcomes for residents of Isle of Wight and Southampton counties were not significantly above or below the statewide average. The premature death rate in Southampton County was higher than Isle of Wight’s and the state average but lower than Franklin’s, and both counties reported a significant lack of primary care physicians and dentists compared to the state average. Full results for each county and city in Virginia can be found at www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/virginia/2018/overview by using the “select a county” drop down menu.

When asked about possible explanations for the overall health disparities and racial disparities in Franklin compared to the rest of Virginia, Dr. Christopher Wilson, director of the Virginia Department of Health’s Western Tidewater Health District, said that health disparities, including racial disparities in health outcomes, exist within every state and within most localities, including Franklin.

“These disparities serve as a starting point to gather and evaluate more thorough or reliable data, which the health district works to do in collaboration with the community by way of the Franklin-Southampton Community Partnership. The next steps include ongoing work toward Community Health Improvement Plans.”

A Community Health Improvement Plan takes into account a community’s unique strengths and weaknesses and outlines key areas where the community can work together to make progress on improving health. While not a formal CHIP, Wilson gave the example of the Western Tidewater Diabetes Coalition, where multiple agencies including the Western Tidewater Health District, Sentara Obici Hospital, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Franklin-Southampton Charities, the Obici Healthcare Foundation, the Western Tidewater Free Clinic and other local partners are working together to address the high rates of diabetes in the area. The main goal of the coalition, he said, was to get more people screened for diabetes in Western Tidewater so they can be referred to care sooner, thus preventing complications and hospitalizations.

“We stand a better chance of successfully tackling tough issues, such as racial disparities in health outcomes, equitable access to quality healthcare, access to healthy foods and safe, connected communities by working together on common goals,” Wilson said.