‘A courthouse is more than a building’

Published 5:24 pm Friday, July 1, 2016

COURTLAND

Appropriately, author John O. Peters’ lecture about Virginia courthouses took place inside the one for Southampton County on Sunday afternoon. Before an audience of 27 guests, Peters outlined the importance that courthouses have figured in Virginia’s culture through the centuries.

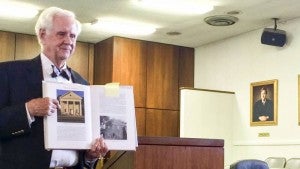

John O. Peters points to the Southampton County Courthouse as it stands now, pictured in his book, “Virginia’s Historic Courthouses.” At right is the building before existing additions. He spoke on the topic of courthouses at the Southampton site on Sunday afternoon. — Stephen H. Cowles | Tidewater News

“The Virginia Courthouse — More than a Building, with particular emphasis on the Southampton County Courthouse,” was the theme of his presentation, which was sponsored by the Southampton County Historical Society.

Indeed, Peters began by saying, “A courthouse is more than a building … it represents a culture.”

Those in Virginia, are “unparalleled in the nation … every state is envious,” he added, noting that our courthouses are all quite distinct, particularly in style.

In 1995, University of Virginia Press published “Virginia’s Historic Courthouses,” co-written by Peters and his wife, Margaret T. Peters.

“My wife and I had written about the courthouses in the Richmond area,” he said. “She worked for the state Department of Historic Resources. I had practiced law for over 30 years and had an ongoing interest in courthouses.

“I think that University of Virginia Press was always interested in us writing a book [on the state courthouses].”

He added that some factors came together for the book to become a reality, and figures to have driven 13,000 miles in Virginia to photograph the buildings in all seasons.

Peters said that just because a courthouse is not considered architecturally significant doesn’t mean it’s not historically significant.

“A community that has a pulse beats on a courthouse green. They [courthouses] reveal the view that people have of justice and rule of law,” he said.

As early settlers made their way in the commonwealth, the first three public buildings were churches, courthouses and jails.

Peters noted that Preservation Virginia considers courthouses to be among the most endangered resources, and he added his surprise that Southampton County was not represented at a recent symposium about the buildings.

There are tough issues facing courthouses, beginning with security, which he acknowledged is of “tremendous importance. You need to secure judges, inmates and people [who work there or attend trials].”

Creating access for the handicapped has also changed the way courthouses are designed.

Parking and convenience have an influence, siting (where it’s going to be placed) and money as a factor is also particularly important.

Peters said he’s witnessed disputes in other localities involving courthouses that were the subject of restoration or being rebuilt elsewhere.

The key to resolution, he said, is “People of good will must be prepared to leave their egos at the door.”

Vitriol and surly remarks that he’s observed are not needed.

“Preserving an old courthouse is not without challenges,” Peters added.

Lynda Updike, of the Society, said there’s been a debate among members of the historical society about whether or not Southampton’s courthouse is historical.

There’s no question in Peter’s view that building is historical, adding, “How can you say it isn’t?”

At one time, the building was eligible to be on the National Register of Historic Places, but apparently nobody applied to have it listed; the deadline was in 2010. Updike later confirmed what Peters said that too many internal additions and alterations had been made to the building, thus disqualifying it from further eligibility.

In the discussion about whether or not to renovate and expand the Southampton Courthouse or build a new one, he said “both are perfectly responsible. I’m not coming down on one side or another.”

Cost-wise, Peters said, the options are fundamentally the same.

“You’re playing with fire to move it. If the pulse beats at Courtland because of the courthouse, if you move it, the pulse will no longer beat there,” he said. “It’s unlikely because of the absence of the tradition and culture and history that it’s ever going to be beat anywhere else.”

Updike said, “I very much want to see the courthouse remain in Courtland. If it doesn’t, Courtland will otherwise wither on the vine. I agree with him on that: The courthouse has a pulse.”

He recommends that people study options, consider the heritage, become involved and take a stand.

Should the courthouse be moved, it’s important to repurpose the old one. To do so will take money, imagination and public support, Peters said, adding, “Don’t go in without your eyes wide open.”

He was asked by an audience member which courthouses he thought were architecturally significant. Because of the number, Peters said he was reluctant to do so, but noted ones in Hanover and Charlotte counties, as well as the one in Petersburg.